Mention Bob Dylan and the spiritual path and most people think of his most controversial career move–turning into a fire breathing evangelical Christian. For many fans the trio of albums he released between 1979-1981 represent the embarrassing nadir of a genius gone temporarily mad.

Personally, I like a lot of the music on Slow Train Coming, Saved and Shot of Love. But I see the records as religious artefacts more than spiritual tomes. At their worst, Dylan comes across as preachy and shrill, his message, blunt and antiseptic. Ironically, Dylan’s ‘Christian period’ accounts for some of his least spiritual music.

As with Van Morrison and Leonard Cohen there is a lode of spirituality that runs deep through most of Dylan’s art. His early protest songs are not dissimilar to Old Testament rants against the ungodly. Virtually the whole of Blood of the Tracks (1975), with songs like Idiot Wind, Simple Twist of Fate and Shelter from the Storm, is a compendium of the many faces of Love. Isis (Desire, 1976), Highlands (Time Out of Mind, 1997) and any number of other tracks across his entire career are lyrical distillations of man’s search for meaning. One of my great favourites, to which I’ve been listening a lot recently, is Señor (Tales of Yankee Power).

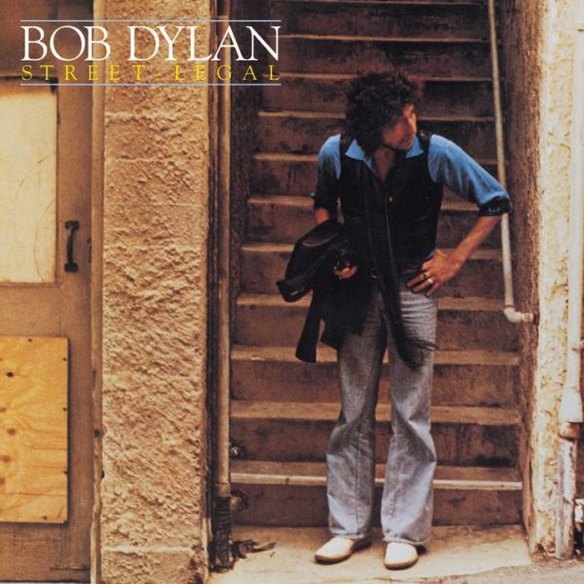

Señor is the high point not just of Street Legal (1978) but, for my money, one of the loftiest pinnacles of his entire career. The song is a tale all right, full of vivid images, pithy observations and some of the greatest lines Dylan ever wrote.

All of Dylan’s great songs are subject to multiple readings and heated debates about their ‘meaning’. I make no claim that my interpretation is definitive. It is not. In fact, I don’t think any work of art has a single ‘meaning’. There are as many meanings as listeners and what follows is my current interpretation of the song.

Given what we now know of Dylan’s spiritual journey in the late 70s—his Rolling Thunder Revue band included several committed Christians; his next album was Slow Train Coming, the first of his three overtly Christian albums–the song seems to be a description of religious conversion. But though this may seem plausible in retrospect, Dylan wraps the moral of his story up in obtuse (but evocative) imagery and words, beginning with the very title of the song itself: Tales of Yankee Power.

There are those (including me, for some years) who try to pick out a story of American ‘bullyboyism’ and military intervention in Central America here. After all, that’s what the song is called! But herein lies the song’s first spiritual truth: don’t get caught up in labels.

This is a song about power, just not political power. And who is this Señor? In Spanish the word means Sir or Master or Lord. A figure of authority. The patron. Let’s say for present purposes, Señor is that shadowy quiet Source that dwells within every person’s soul.

Señor, señor

Can you tell me where we’re headin’?

Lincoln County Road or Armageddon?

Dylan opens with a confused question. ‘Is this just regular life or am I hurtling straight for the end of the world?’ Both outcomes are plausible, at this stage. A drive through a familiar part of town, or Doomsday.

Seems like I been down this way before

Is there any truth in that, señor?

The singer tries to reassure himself there is nothing to fear. ‘I’ve seen this movie before.’ But the doubt keeps nagging. ‘Can you just confirm that, for me Senor? I’m going to be ok, right. Just like all the other times.’

Whether we like it or not. Whether we know where we’re heading or not, we are on our way. Señor is riding out ahead and we’re feeling a bit irritable.

Señor, señor

Do you know where she is hidin’?

How long are we gonna be ridin’?

How long must I keep my eyes glued to the door?

Will there be any comfort there, señor?

Throughout my life my dreams have included a mysterious and powerful woman. When I was a teenager she was lithe, and when I was an adult she was motherly. Sometimes she was gentle, other times she screamed at me. Once, as an old hag, she revealed the entire Universe in an instant. But in all her guises I could never touch her. She was just out of reach. And I wake longing to see her again.

The song’s second verse is a perfect summation of that experience. In Dylan’s case perhaps this verse refers to his Muse. The 1980s were just around the corner. And for most of that decade he struggled to find the flow of words and images that seemed to come so effortlessly in the 60s and 70s. The 80s—revisionist thinking notwithstanding—are considered to be the weakest period of Dylan’s career. And here in 1978 he’s digging deep: do you know where she is hidin’? He’s on the brink of a crisis.

There’s a wicked wind still blowin’ on that upper deck

There’s an iron cross still hanging down from around her neck

There’s a marchin’ band still playin’ in that vacant lot

Where she held me in her arms one time and said, “Forget me not”

The third verse’s imagery is cinematic and surreal. You can feel the wild wind howling against your body and see the hypnotic swing of that heavy iron cross. You can hear the creaking of the wooden decks of a ship tossed on the high seas. And then there’s a marching band playing for nobody. This is like a scene from a Bergman film in which She greets him with a delicate kiss which in actuality turns out to be a kiss-off, instead. What irony in those three words, ‘Forget me not’. Dylan hasn’t forgotten her, but she has done the dirty on him and is nowhere to be found.

Señor, señor

I can see that painted wagon

Smell the tail of the dragon

Can’t stand the suspense anymore

Can you tell me who to contact here, señor?

The tension is building. Our troubled narrator is scared and freaking out. He senses the monster around a gypsy’s wagon. He can smell danger. It’s lurking, but where exactly? The suspense is killing him. His panic is palatable. Cold sweats have broken out. Can you tell me who to contact here?

Well, the last thing I remember before I stripped and kneeled

Was that trainload of fools bogged down in a magnetic field

A gypsy with a broken flag and a flashing ring

He said, “Son, this ain’t a dream no more, it’s the real thing”

The singer is brought to his knees (in desperate supplication?) and then he blacks out. But just before he does he gets the bad news he’s dreaded for so long. That dragon-loving gypsy who has snared hundreds of foolish souls like his, cackles, Son, this ain’t a dream no more, it’s the real thing.

Señor, señor

You know their hearts are as hard as leather

Well, give me a minute, let me get it together

Just gotta pick myself up off the floor

I’m ready when you are, señor

Confusion, betrayal and revelation are followed by resignation. The nightmare scenario turns out to be true. There is no point in resistance or even prayer. All the remains is to pull yourself up off the floor and proclaim, ‘I’m ready’. For whatever comes. ‘I submit, my Lord.’

Señor, señor

Let’s overturn these tables

Disconnect these cables

This place don’t make sense to me no more

Can you tell me what we’re waiting for, señor?

And once the decision has been made, once the point of no return is passed, a certain eagerness washes over the soul. Like Christ overturning the tables of the moneychangers in the Temple, it’s time to rip the cables from their sockets, turn off the lights and step into the unknown Next. That familiar place—Lincoln Country Road–where everything made sense is no more. ‘What are we waiting around for?’

Much has been made of Dylan’s influences—everyone from Rimbaud and Woody Guthrie to Jesus and Blind Willie McTell—and in Señor I hear echoes of John Donne’s beautiful but brutal holy sonnet, Batter my heart, three-person’d God (1633).

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new

Both poems share a sense of violence, foreboding and overpowering spiritual lust. Of wanting to be brought completely to one’s knees and to absolute surrender to Señor.

The critics were lukewarm to scathing of Street Legal. The musical pandits Christagau and Marcus labelled it ‘horrendous’ and ‘unlistenable’. But as Dylan reminded us way back when the times are always changing and today Street Legal is considered a diamond in the rough. Not as brilliant as his best but certainly superior to the original debunking it received.

Regardless of the critics, Dylan’s peers have always found Senor (Tales of Yankee Power) to be a powerful creation. There are a multitude of covers available on the internet from all sorts of angles. Here are three that are particularly good.

Let’s start with a live version from the man himself from 1978.

Willie Nelson and Tucson’s Calexico give an absolutely stunning, Tex-Mex interpretation in the Dylan bio-pic I’m Not There. Nelson’s elastic and worn vocal style is counterbalanced by a sweet Mexacali trumpet trio and his familiar pick/strumming guitar work.

Diva de Lai is a group that combined heavy rock with opera to give expression to their love of Bob Dylan! Karin Shifrin, classically trained opera star sends chills down your spine in this version which takes the songs inherent dramatic, spiritual tension to Himalayan heights!

There was probably no bigger fan of Dylan in the music world than Jerry Garcia (or Joan Baez or The Band or…) He covered many of Bob’s songs throughout his career with Senor being one of favorites. This is a loving straight ahead telling of the story, nothing fancy but solid and full of Garcia’s characteristic guitar magic.